Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

The Ogham alphabet looks, at first glance, like a row of simple notches and tally marks. Yet on closer inspection those strokes record real names, places, and phrases from early medieval Ireland.

What seems like scratches on stone is in fact a writing system with rhythm and design.

This guide will walk you through what Ogham is, how the letters work, and a straightforward routine you can use to start reading it yourself.

The Ogham alphabet was used mainly in Ireland and parts of western Britain between the 4th and 7th centuries.

Instead of being written left to right like Latin, it runs along the edge of a stone, with the edge itself acting as the stem line.

Each letter is made of one to five short strokes crossing or touching that edge. Most inscriptions record personal names, kin groups, or territories, which makes them some of the most direct voices from that period.

Hundreds of these stones still stand in places like Kerry, Cork, and Waterford, and archaeologists continue to catalog them.

Later, medieval scribes preserved the script in manuscripts, which means Ogham survives in both carved stone and written form.

Because those sources belong to different contexts, it’s useful to note whether you’re looking at an original stone in the landscape or a later copy in a book.

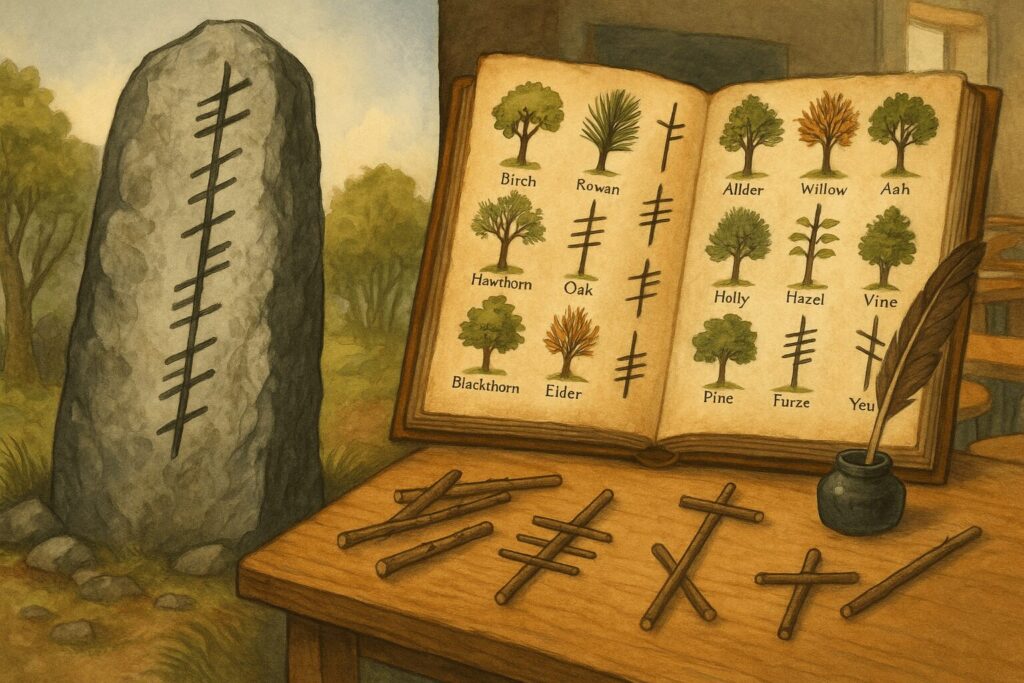

The Ogham alphabet has twenty main letters, called feda.

They’re divided into four groups of five, known as aicmí. Each group has its own “direction”: strokes on the right side of the edge, strokes on the left, strokes crossing the edge, or small notches cut into the edge itself.

Later on, scribes added a few extra letters (forfeda) to capture new sounds as the language changed.

So, for example, if you spot three short strokes cut to the right of the edge, you know you’re looking at the third letter from that family.

Thinking in terms of these patterns makes the script easier to read than trying to memorize a flat list of symbols.

It also shows why Ogham is such a perfect fit for stone edges and wooden staves, it was literally designed for them.

On most Ogham stones, the writing begins near the base and runs upward along the edge. Sometimes, though, the inscription curves over the top and continues down the other side.

That’s why the first step is always to trace the perimeter with your eyes and look for signs that show where it starts and ends – things like crosses, dots, or breaks between names.

When working from photos, it helps to sketch a faint arrow showing the reading direction so you don’t lose track.

Here’s a quick example: imagine an edge line with four short strokes cut across it. In Ogham, that belongs to the “across” family, and since it’s the fourth letter in that group, it gives you the sound “S” in most charts.

A lot of people search for “Ogham runes alphabet”, but that phrase is a mix-up. Runes come from the Germanic world, while Ogham is Gaelic.

The scripts look different, they come from different traditions, and they mark different sounds. So when you see “Celtic Ogham alphabet” or “Gaelic Ogham alphabet”, it’s pointing to the Irish and Scottish system, not Norse runes.

They both belong to the early medieval period, but they’re more like distant cousins than twins.

That distinction is important if you’re writing blog posts or labeling images. Search engines blur the terms together – but your readers don’t need the same confusion.

You’ll often come across charts linking the Ogham alphabet to trees – birch, oak, and so on.

This idea comes from medieval glosses, where scribes tied each letter name to a plant. It’s a clever memory trick, and it works beautifully in classrooms or creative projects.

But the oldest Ogham stones don’t spell out tree codes. They record names of people, kin groups, and places.

That’s why it makes sense to treat the tree lists as a later teaching tool rather than as proof that early inscriptions carried hidden “tree messages”.

EEach Ogham letter stands for a sound from early Irish. Because pronunciations shifted over time, the tables in manuscripts don’t always match perfectly with what we see on stones.

To keep things simple, here’s the version most learners start with:

So, if you see a single notch on the edge, that’s A. If you see three notches, that’s U. This chart is the one you’ll find in most beginner guides, and it’s more than enough for practice inscriptions or classroom demos.

If you’ve got a photo or rubbing of an Ogham stone, here’s how to read it.

First, trace the edge with your finger or pencil so you know where the inscription starts and ends.

Second, sort the strokes into their families: lines on the right, lines on the left, lines across the edge, or notches on the edge.

Third, count the strokes and match them to letters using a basic chart. Finally, sound the letters out and look for common Old Irish words like MAQI (“son of”) or MUCOI (“of the tribe”).

If you just want to practice without a stone, use a manuscript table like the one in the Book of Ballymote. Just note in your records that you’re using a manuscript chart, not a carved example, so you don’t confuse the two later.

For field days and museum trips I carry a pocket notebook with weather-proof paper so pencil marks survive rain. This is the one I use, check it out if you’re interested: Field Notebook.

The Ogham alphabet wasn’t only carved on stones. In the Middle Ages, scholars also used it in books – for teaching, puzzles, and ciphers.

In Scotland, people later kept the letter names alive through poems and charms. Because these manuscript uses came long after the first stone carvings, I treat them as “school Ogham” in my notes.

That way, it’s clear why you might see a tree name in a manuscript chart but not on an early stone.

A fun way to get hands-on with the Ogham alphabet is to make a simple name tag. Grab a strip of cardstock and draw a center line down the middle – that’s your stem.

Then write your first name in Ogham by adding short strokes across the line. Keep the strokes spaced out, and mark the starting point with a small triangle so it’s obvious which way to read.

Since Ogham letters are based on stroke count and position, even beginners can create something that looks authentic.

If you want to imitate the look of carved stones, turn the card sideways and let the letters climb up the edge.

For photos, you can place the tag next to a branch or leaf linked to your first letter – this gives a nice Celtic Ogham alphabet feel without pretending it’s some secret code.

One common mistake is assuming Ogham inscriptions always read upward. Many do, but some wrap around the top or even flip.

That’s why it’s important to trace the path with your eyes before deciding where the text begins and ends. Another mix-up is treating the Ogham alphabet as if it were always tied to Druidic plant codes.

In reality, those tree associations came from later teaching glosses, not the oldest stones.

Finally, people often trip over the Q-rune, thinking it represents “KW” for modern English names. It doesn’t.

So if you want to write your name in Ogham, treat it as creative art rather than a strict translation exercise.

Is Ogham Irish or “Celtic”?

Ogham started in Ireland and later spread into parts of western Britain. Calling it the “Celtic Ogham alphabet” isn’t wrong since it belongs to that wider world, but “Irish Ogham” is the most precise.

Can I write modern English with Ogham?

You can get close, though some English sounds don’t line up cleanly. It works best for simple names, and it’s easier if you drop silent letters.

What about the tree list?

That comes from medieval manuscripts where each letter was linked to a tree. The oldest stones don’t use it as a secret code, so treat the tree list as a teaching aid or a creative layer, not ancient hidden lore.

Does “Ogham runes alphabet” exist?

No. That’s a mix-up. Runes are Germanic, Ogham is Gaelic. They’re cousins in time, but not the same script.

By now you’ve seen how the Ogham alphabet was carved along stone edges, how the letter families help you memorize the system, and how to follow the reading direction in real inscriptions.

You’ve also learned where the Gaelic Ogham alphabet appears in manuscripts, why the famous “Ogham tree charts” come from later teaching traditions, and why it’s a mistake to confuse Ogham with Germanic runes.

So here’s your next step: grab a photo of an Ogham stone, mark out the letter families, and sound out a name.

The strokes are simple, the system is logical, and you’ll probably get your first successful reading right away. Once you’ve done that, you’ll be able to explain Ogham with confidence instead of confusion.